Mr. Fallah was 4 when he left Iran after its revolution. Now, he’s using his art to support the recent uprising there.

Amir H. Fallah was born in Iran in 1979, the year that a revolution overthrew the country’s monarchy and replaced it with an Islamic republic. He left with his family when he was 4, and they eventually settled in the United States.

Now a contemporary artist based in Los Angeles, Mr. Fallah makes richly ornamental works that merge his two worlds. They combine the themes and patterns found in Persian myths, miniatures, and carpets with motifs from Western pop culture, cartoons and graphics.

Mr. Fallah has had a busy few months. His most recent solo museum exhibition runs through May 14 at the Fowler Museum at the University of California, Los Angeles, which Mr. Fallah attended.

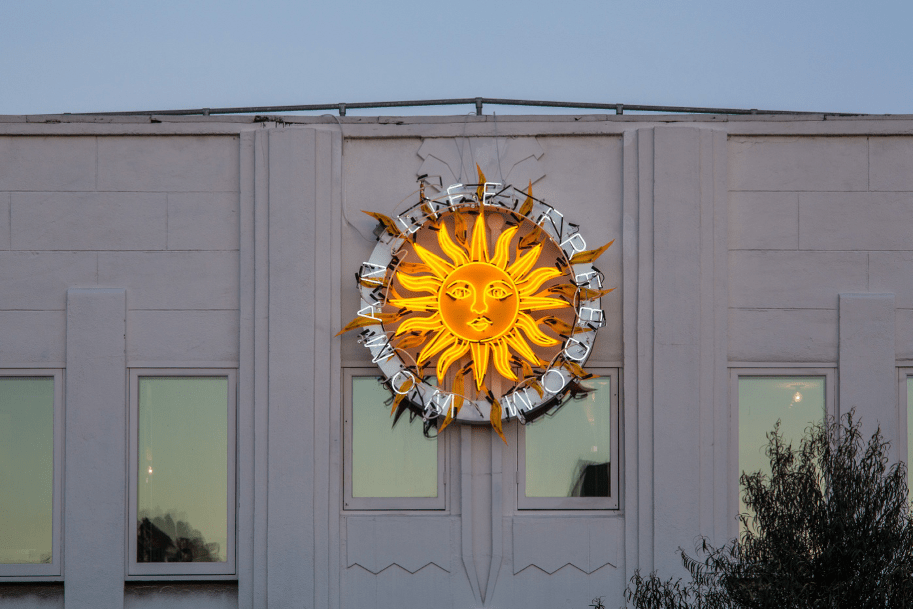

In February, he presented an outdoor artwork in Los Angeles inspired by what he described as a second Iranian revolution: the uprising sparked in September by the death of Mahsa Amini, a 22-year-old Iranian woman, while in the custody of the morality police. She had been arrested on the grounds that she was not observing Iran’s mandatory hijab law. Titled “Chant,” it’s a neon sun with the features of a woman and the uprising’s slogan, “Woman, Life, Freedom,” beamed around it in English, Farsi, and phonetically spelled Farsi.

CHANT neon artwork, 2022 displayed on Shulamit Nazarian gallery facade. Courtesy Of The Artist And Shulamit Nazarian, Los Angeles.

At Art Basel Hong Kong, Mr. Fallah is taking over the booth of the Denny Gallery, a first-time exhibitor, with five paintings. The centerpiece is a monumental work that depicts the battle between good and evil. It shows an amorous couple and cartoon characters, with dragons, menacing demons, and veiled figures.

In a recent telephone interview from Los Angeles, Mr. Fallah spoke about the Hong Kong work, his life and trajectory, and the uprising in Iran.

This conversation has been edited and condensed.

What inspired the monumental work you created for Art Basel Hong Kong?

All of my work comes out of issues dealing with immigration, being a refugee, and living in a hybrid culture. But once I started watching the protests in Iran, I really felt compelled to make a body of work that addressed them more specifically. It was just something that was top of mind. So, I shifted gears.

The work is open enough to talk about the broader themes of the struggle for democracy and basic human rights as a whole, because I don’t think this issue is isolated to Iran. Hong Kong certainly has had its own bouts of protests and issues around democracy. Democracy is getting attacked no matter where you are, and as humans, we have to constantly be vigilant.

Where do the images in your works come from?

I have a very large database of thousands of images from a wide array of sources — from Persian miniatures to 1930s cartoon strips to images that I find in digitized public libraries all over the world. I might find something on Instagram that somebody posts and save it, or something in the digitized British Museum archive. I go through databases and pull images, and much like a puzzle, start trying to fit them together to create some sort of narrative or story.

How has the Iran protest movement affected you?

On a very personal level: I have lots of family in Iran, all over the country, including several cousins in Tehran who were born after I left. There’s this sense of hopelessness and desperation that all young people have there.

Speaking to my cousins in Tehran, I asked, “What can I do from here?” The number one thing that they said was: Amplify our voices. Let people know what’s going on in Iran.

In the American media, you barely see any mention of what’s happening in Iran, which is shocking, because it’s the biggest feminist movement ever.

I felt like I needed to do something. I couldn’t not do it.

Amir H. Fallah, The Ballot or the Bullet, 2022. Acrylic on canvas. 60 x 60 in.

Would you describe what we are witnessing right now as a revolution?

I would describe it as a revolution. My father was, like many Iranians, a supporter of the 1978-79 revolution. He thought he was bringing in democracy.

And then once it happened, he realized that the wool was pulled over his eyes and that he was tricked.

When I speak with people like him, who lived through the first revolution, they say this is how it started. There were ebbs and flows; it was not an overnight thing. I think there’s a boiling point where everyone has had enough. And when you have nothing to live for, you’re willing to die for freedom. It’s just a powder keg waiting to explode.

You were 4½ years old when you left Iran. Why is being Iranian so central to your identity?

All of my work comes out of my disconnection and desire for connection with Iran. I feel like I have to respond to what’s directly affecting me.

No one meets me and thinks I’m American. Even though I sound American, they see my name, they look at the color of my skin and immediately say, “Where are you from?” So, I’m always reminded on a daily basis that this is not my place of origin. I always feel like I’m in cultural limbo. Every immigrant, regardless of where they’re from, feels a strong pull back to their culture of origin.

I make art about my own personal experiences, only because I know myself best. I want to make work that’s a marker for this time, for this moment, where, 100 years from now, maybe somebody looks at one of my paintings and says, “This is what it must have felt like to be an Iranian living in America during this moment.”

Amir H. Fallah in his studio in California. He is showing five pieces at Art Basel Hong Kong. “All of my work comes out of issues dealing with immigration, being a refugee, and living in a hybrid culture,” he said.Credit...Maggie Shannon for The New York Times

Do you hope to be able to go back to Iran in the not-too-distant future?

Absolutely. I think about it all the time. I have a 7-year-old son. He’s half Iranian, half Puerto Rican. I would love to take him to Iran. My wife is dying to go there, and I’m dying to go there. I only have faint memories of my country. Iran is one of the oldest places in the world. It’s got such a rich history and such incredible culture, food, art.

Yet, I want to experience the place where I was born as a free person. I don’t want to go there and be depressed, and feel sorry for the population. I want to go there and really enjoy it the way it’s meant to be enjoyed, and see family. The second I can, I will.